TAKUDZWA HILLARY CHIWANZA

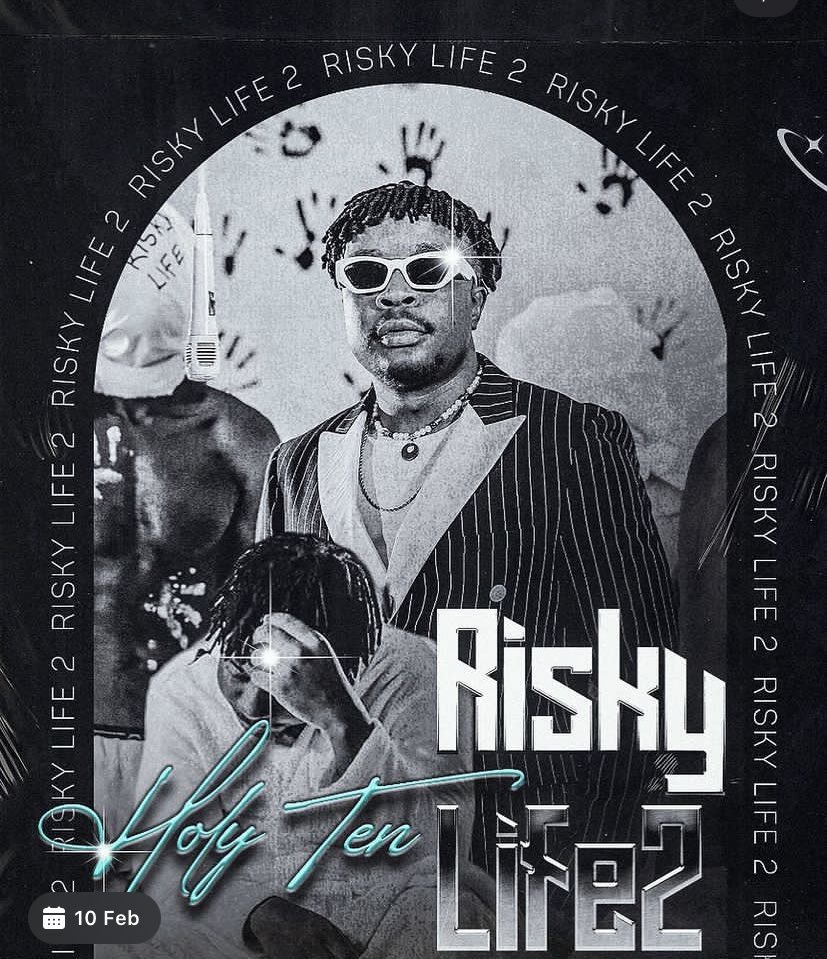

THE placement of Holy Ten in Zim Hip Hop has an intriguing aspect to it for the simple reason that he is one of the foremost artists who played a huge role in opening up the genre to wider audiences; lifting rap sounds in Zimbabwe from obscurity to domineering prominence in a spectacular fashion that greatly captivated many. And also irked many, in equal measure. He fearlessly paved the way. And his unrelenting presence in the game at this conjuncture thus rests on this premise – he feels he is the unrivalled overlord of Zim Hip Hop; one who should not be intensely scrutinized since he fervently believes he can get away with anything. One could say that his primary goal, as reflected in his strident work ethic – and against the backdrop of his undeniable nationwide appeal, status, and influence – is to keep this ‘lordship’ reality an immutable one. As such, the release of his latest February 2024 album Risky Life II should viewed in this context.

A sequel to his 2021 pioneering album Risky Life, Holy Ten emerges and positions himself as the successful rapper Zimbabwe never had, seeking further relevance by chronicling the tales of a rather precarious lifestyle that comes with the fame. He is by all accounts the poster-boy of the newfound though unstable glitz and glamour that Zimbabwean celebrity artists have been basking in of late; animated by the rush for material wealth as the sine qua non of creative relevance. Risky Life 2 attempts to show a grown-up Holy Ten who has gone through countless pleasant and horrendous experiences in Zimbabwe’s music industry and public domain ever since he burst to the national stage circa 2020, and in this aspect the album performs fairly well. The aura of a responsible man who perceives his persona as the embodiment of astute leadership in the professional, domestic, and social dimensions of life cannot be shaken off. However, this projection of Holy Ten as the unparalleled king of all, abetted by his usual braggadocio, gets undone by a conceptual framework that seems rushed and a tad recycled.

But from another angle, he cannot be faulted for this. His quest at this stage in his career is one predicated on the imperative to make maximum returns in the shortest time possible. In this way, he hopes to stay one step ahead of his competition (encapsulated in the track One Step Ahead in the album) and thwart any perceived threats. But such a stance does a major disservice to the album. At certain points, it seems like a mere collection of songs whose motifs revolve around the same issues, and at other points it comes off as the best project perfectly suited to open the year for Zim Hip Hop and the Zimbabwean music industry at large.

Such is Holy Ten – he never hesitates to move with the frenetic energy of an unquestionable I’m-the-boss-so-you-can’t-touch-me attitude; and yet, in other instances, this overbearing pride wears him down and he gets nervy. Perhaps that is the essence of a risky life – having the mettle to go through all sorts of emotions that come with being a famous artist, without losing one’s sanity; even when boldly professing loyalty to the ruling establishment as shown in the track Mureza featuring Poptain.

A praiseworthy feature of [relatively] progressive artistic maturity exhibited by Holy Ten in the new album Risky Life II is the conspicuous elevation of impressive levels of music production. Other artists in Zimbabwe could have solid conceptual outlines and story structuring for their projects but get short-changed by not investing enough drive, passion, and tenacity in production quality. For Holy Ten, this is not the case. The admirable production on Risky Life 2 gives Holy Ten a major lifeline that is not to be underestimated. Because when such production meets the making and release of the music video, there is an undeniable element of longevity that his music can rest on.

Which brings us to the point that Holy Ten’s insistence on accompanying an album release with visual content is one worth taking note of – it makes his music greatly palatable even in instances where his lyrical content might not be the most impeccable out there. So, all he has to do now is bank sufficient reliance on his established fan-base. He knows and understands his audience – and when listening through the album, despite how good it feels on the ear, there are instances where it feels as if all he had to do was the bare minimum for him to solidify his status and influence in Zim Hip Hop.

The majority of the songs in Holy Ten’s latest album Risky Life II run at an average of two-minutes-and-something-seconds only – revealing the undercurrents of doing only the bare minimum in order to maintain relevance and status in the game. The laudable thing though is that making such curt tracks works effectively well for him. His booming vocal projection and delivery give him room to detail his stories in lines that should not exceed three minutes. But to stand on this assertion might give him a free-pass to impunity – the total running time of Risky Life II is 30 minutes, and it denies Holy Ten the “completeness factor” he needed to execute for the album to truly feel like a Long Play.

Sometimes, the stories he wants to paint of a “risky life” – now that he is doubly famous, controversial; married; striking a balance between familial responsibilities and professional/social obligatory functions; subject to tight schedules in certain instances; and negative perceptions of his allegiance to the ruling establishment – such stories get obfuscated in that his tracks are just too short. The project is denuded of the innovation and broadened perspectives it sorely needed in this aspect. And to this end one may subscribe to the notion that the album is mid, a pejorative, nonchalant term conjured by netizens to describe artistic work that shows potential yet ultimately stutters when held to the highest standards of rap excellence. But this is all good, nonetheless. Holy Ten, through his haughty lyrical content (which we allow him to air without qualms because freedom of expression is the fundamental pillar of rap) does not simply care – in the opening track Secondary School he gives a predictable vindication for his quirky and divisive behaviour as a trait forged in the crucible called secondary education, cemented, and inherited without alterations into his adulthood. Bitterness. Notwithstanding this, it is a befitting intro.

Even though Holy Ten seems to be recycling the same motifs with small iterations here and there, he performs well in bringing out the figurative sense of a “risky life” – the risky life he delivers with impassioned fervency on well-laid instrumentals is not only a reference to his lifestyle and lived reality. This risky life also extends to the generality of the country’s youthful populations, the majority group consuming Holy Ten’s music. His mastery in narrating stories of decadence, unchecked sexual escapades, unbridled substance abuse, crass materialism/consumerism, and irresponsible decision-making is enviable. He speaks the stories of lots of youths in the country. Because in solidifying his status as the country’s inimitable rapper, he also sees it as his duty to exhort fellow youths to just take it easy sometimes.

It is what makes his music easily relatable, in the final analysis. The paradox of glorifying precarious lifestyles while at the same time castigating the excesses of such risks (emotional and physical through our actions and daily pursuits) remains a sticking point in Holy Ten’s discography – but, clearly, he relishes such a pattern of story-telling without minding about stringent rap academics. Most notably, we love the creative chemistry he effortlessly shares with Kimberly Richards, his wife, because their collaborations bring the best out of them from a purely musical standpoint. Evidently, his spouse is a reliable witness to the ubiquity of “risky lives” surrounding them on a domestic and public level.

But the most noteworthy collaboration is undoubtedly Jongwe featuring Kayflow – the latter being a remarkably gifted and steadily rising rapper in Zim Hip Hop spaces. Jongwe is a cool track, and we use cool here in the wholesale sense of what the word engenders, because the song graphically details – without prevarications – the undesirable characteristics of a risky life mostly experienced in the urban areas (ditto the big city and bright lights) which usually befalls young men when they start earning a little more material gains in life. The loveliest thing about Jongwe is that Kayflow fully brought to the table his A-game, maximizing this opportunity to increase his visibility and imprint in Zim Hip Hop and Zim music at large. By the time he signs out with “Wepajecha!”, listeners are left wanting more. On a laid-back, slowed, infectious yet emotionally-charged instrumental, the two rappers show how imposing, grandiose, and brilliant Zim Hip Hop has come thus far. One cannot resist but fall in love with Kayflow’s witty wordplays and intelligent use of metaphoric language. By roping in Kayflow, Holy Ten maintained his ideal trait of putting other rappers on at a time when critics assert that he is increasingly becoming selfish with the game given his fall-out with fellow rappers in the previous years.

For all his imperious posturing through bumptious bars, the theme of paranoia – the peak aspect of the proverbial risky life – completely engulfs him just after he warns Jongwe to lead a responsible life, and towards the close of the album. The tracks Paranoia, Baba Vasina Basa, Are You Really Leaving?, Party Rules and the ostensibly misplaced interlude lay bare with sufficient clarity his insecurities in light of his status. What is expected of him? What advice should he give to the scores of his fans? How should he navigate contradictions and disagreements with his wife? His spirituality? Social standing? Will they play my album? Etc, etc, etc. This emotional foray into deep-seated feelings of paranoia that are always veiled by his larger-than-life persona as Mr. Holy aka Mujaya earns him some empathy and sympathy from listeners. You will almost forget that he once proclaimed the supercilious claims that he can body Jay-Z; referred to other fellow rappers as his sons; and takes great pleasure in pejoratively name-dropping Winky D in his songs. But, that’s just Holy Ten for you.

Holy Ten’s fans will comfortably assert that this is one of his stronger bodies of work since the first instalment of Risky Life. There are certainly some big moments in the album. That is a given. The run from the first to the fourth track is special – but then it becomes a little all over the place from that point until you get to Jongwe, with Kayflow shining on that record. The album itself does not have a concretely felt sound with a distinctly clear direction. It does feel like a step back for his album story and progression. Holy Ten generally loves to knead in rap and a mishmash of other related sounds, and this is the feel that Risky Life II exudes. The album has some of the best songs of his career in terms of how mature, poised, and confident he sounds – with such traits being evident in Banga, One Step Ahead, Jongwe, and Baba Vasina Basa.

Whether this newfound maturity is sincere or performative, it is commendable enough; and encouraging, too, although this diverges from how he carries himself outside the booth. On his sixth full-length body of work, Holy Ten struggles to say anything strikingly novel. He finds refuge in stating the same concerns, a familiar pattern that undercuts his sincerity – running the dreaded risk of becoming monotonous. But that is that. Holy Ten is here to stay, and flex. And this album will aid such a quest – to solidify his massive status, appeal and influence. Even where it is incontestable that more could have been done; better stuff could have been delivered. In any case, his consistency and prolific work ethic will always make the name Holy Ten endure.

♦ALBUM RATING – 6.5/10

You can listen to Risky Life II by Holy Ten is now available on different digital streaming platforms.

And you can watch the videos on his YouTube:

0 Comments